Giant Wild Goose Pagoda

The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, officially known as the Ci'en Temple Pagoda, is located within the Da Ci'en Temple in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China. This magnificent seven-story square brick pagoda was first built in the Tang Dynasty under the supervision of the famous monk Xuanzang to store the Buddhist scriptures and statues he brought back from India. As one of the symbolic buildings of the ancient capital Chang'an, the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda is not only a model of ancient Chinese pavilion-style pagodas but also a grand testament to cultural exchange between China and other countries, reflecting the glorious achievements of Buddhist architecture in the Tang Dynasty.

- 名称

- Giant Wild Goose Pagoda

- 时期

- Tang Dynasty

- 地区

- Shaanxi

- 地点

- Xi'an, Shaanxi Province

- 标签

- Pagoda, Tang Dynasty Architecture, Xi'an, Buddhism, Pavilion-style Pagoda

Introduction

The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda is a seven-story, square, pavilion-style hollow brick pagoda from the Tang Dynasty and is a national key cultural relic protection unit. Also known as the Ci’en Temple Pagoda, it served as the scripture storage pagoda for the eminent monk Xuanzang. It is located within the Da Ci’en Temple in the Jinchang Quarter of Tang Chang’an City (now the north entrance of Yanta South Road, Yanta District, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province), and it remains one of the important symbols of Tang Chang’an preserved to this day. The Da Ci’en Temple was first built in the 22nd year of the Zhenguan era of the Tang Dynasty (648 AD). It was a royal temple built by Li Zhi, then the crown prince, on the former site of the Wulou Temple of the Sui Dynasty to commemorate the nurturing grace of his birth mother, Empress Wende. According to the “Biography of the Tripitaka Master of the Great Ci’en Temple,” the temple had more than 10 courtyards and a total of 1,897 rooms, with multiple-storied buildings, layered halls, cloud-like pavilions, and meditation rooms. Shortly after the temple was completed, Xuanzang moved from Hongfu Temple to the “translation hall” in the east courtyard of the temple to translate scriptures, where he founded a major school of Chinese Buddhism—the Ci’en School. In the third year of the Yonghui era (652 AD), Xuanzang requested the construction of a pagoda to preserve the scriptures and Buddha statues he had brought back from India. With the approval of Emperor Gaozong, the Wild Goose Pagoda (commonly known as the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda) was built in the west courtyard of the Da Ci’en Temple. Xuanzang “personally carried baskets and transported bricks and stones, and the work was completed after two years.” After the Tang Dynasty, the temple was repeatedly damaged by wars.

Historical Documents

Preface to the Holy Teachings of the Great Tang Tripitaka

大唐三藏圣教序

Preface to the Holy Teachings of the Great Tang Tripitaka

太宗文皇帝制

Composed by Emperor Taizong Wen

盖闻二仪有像,显覆载以含生;四时无形,潜寒暑以化物。是以窥天鉴地,庸愚皆识其端;明阴洞阳,贤哲罕穷其数。然而天地苞乎阴阳而易识者,以其有像也;阴阳处乎天地而难穷者,以其无形也。故知像显可征,虽愚不惑;形潜莫睹,在智犹迷。况乎佛道崇虚,乘幽控寂,弘济万品,典御十方!举威灵而无上,抑神力而无下。大之则弥于宇宙;细之则摄于毫厘。无灭无生,历千劫而不古;若隐若显,运百福而长今。妙道凝玄,遵之,莫知其际;法流湛寂,挹之,莫测其源。故知蠢蠢凡愚,区区庸鄙,投其旨趣,能无疑惑者哉!

It is heard that the two luminaries (heaven and earth) have forms, manifesting their covering and supporting to contain life; the four seasons are formless, concealing cold and heat to transform things. Thus, by observing heaven and examining earth, even the ignorant can discern their beginnings; by understanding yin and penetrating yang, even the wise rarely exhaust their numbers. However, heaven and earth, encompassing yin and yang, are easy to know because they have forms; yin and yang, residing within heaven and earth, are difficult to fathom because they are formless. Therefore, it is known that manifest forms can be verified, and even the foolish are not confused; hidden forms cannot be seen, and even the wise remain perplexed. How much more so the Buddhist Way, which reveres emptiness, rides the profound, controls tranquility, widely saves myriad beings, and governs the ten directions! When its majestic power is raised, there is nothing above it; when its divine power is suppressed, there is nothing below it. When great, it pervades the universe; when subtle, it is contained in a hair’s breadth. Without extinction or birth, it endures a thousand kalpas without aging; sometimes hidden, sometimes manifest, it brings a hundred blessings and lasts forever. The wondrous Way is profoundly subtle; following it, one knows not its bounds; the flow of Dharma is clear and tranquil; drawing from it, one cannot fathom its source. Therefore, it is known that among the teeming common fools and the petty vulgar, who, when they turn to its essence, can be without doubt?

然则大教之兴,基乎西土,腾汉庭而皎梦,照东域而流慈。昔者,分形分迹之时,言未驰而成化;当常现常之世,民仰德而知遵。及乎晦影归真,迁仪越世,金容掩色,不镜三千之光;丽象开图,空端四八之相。于是微言广被,拯含类于三涂;遗训遐宣,导群生于十地。然而真教难仰,莫能一其旨归;曲学易遵,邪正于焉纷纠。所以空有之论,或习俗而是非;大小之乘,乍沿时而隆替。

Thus, the rise of the great teaching was based in the Western Lands, it soared to the Han court as a bright dream, and illuminated the Eastern regions, flowing with compassion. In ancient times, when forms and traces were divided, words had not yet spread, yet transformation was achieved; in the era of constant manifestation, the people looked up to virtue and knew to follow it. When the shadow returned to truth, and the rites transcended the world, the golden countenance concealed its color, not reflecting the light of three thousand worlds; the beautiful image unfolded, vainly displaying the forty-eight marks. Thereupon, subtle words were widely spread, rescuing sentient beings from the three evil paths; the bequeathed teachings were proclaimed far and wide, guiding all beings to the ten stages. However, the true teaching is difficult to uphold, and none can unify its ultimate purpose; crooked doctrines are easy to follow, and thus right and wrong become entangled. Therefore, the discussions of emptiness and existence are sometimes judged right or wrong according to custom; the Great and Small Vehicles sometimes rise and fall with the times.

有玄奘法师者,法门之领袖也。幼怀贞敏,早悟三空之心;长契神情,先苞四忍之行。松风水月,未足比其清华;仙露明珠,讵能方其朗润?故以智通无累,神测未形,超六尘而迥出,只千古而无对。凝心内境,悲正法之陵迟;栖虑玄门,慨深文之讹谬。思欲分条析理,广彼前闻,截伪续真,开兹后学。

There was the Dharma Master Xuanzang, a leader of the Dharma gate. In his youth, he possessed pure intelligence and early awakened to the mind of the three emptinesses; as he grew, he harmonized with divine feelings, first embracing the practice of the four patiences. The wind in the pines and the moon in the water are not enough to compare to his purity and brilliance; the immortal dew and the bright pearl, how could they match his clarity and luster? Therefore, with wisdom, he was free from hindrances, and his spirit perceived the unformed. He transcended the six dusts and stood out, unparalleled through a thousand ages. Concentrating his mind on the inner realm, he grieved the decline of the true Dharma; dwelling on the profound gate, he lamented the errors in the deep texts. He wished to categorize and analyze principles, to expand previous knowledge, to cut off falsehood and continue truth, to open this for future learners.

是以翘心净土,往游西域。乘危远迈,杖策孤征,积雪晨飞,途间失地;惊砂夕起,空外迷天。万里山川,拨烟霞而进影;百重寒暑,蹑霜雨而前踪。诚重劳轻,求深愿达,周游西宇,十有七年。穷历道邦,询求正教,双林八水,味道餐风,鹿苑鹫峰,瞻奇仰异。承至言于先圣,受真教于上贤,探赜妙门,精穷奥业。一乘五律之道,驰骤于心田,八藏三箧之文,波涛于口海。

Therefore, he set his heart on the Pure Land and traveled to the Western Regions. He braved dangers and journeyed far, leaning on his staff, a solitary expedition. Accumulated snow flew in the morning, and he lost his way; startling sand rose in the evening, and he lost his bearings in the vast sky. Across ten thousand li of mountains and rivers, he pushed aside mist and clouds to advance his shadow; through a hundred layers of cold and heat, he trod on frost and rain to press forward. His sincerity was great, his toil light; his quest was deep, his wish fulfilled. He traveled through the Western lands for seventeen years. He thoroughly visited various countries, inquiring about the true teaching. In the Twin Groves and by the Eight Waters, he tasted the Way and partook of the wind; at the Deer Park and Vulture Peak, he gazed upon wonders and admired the extraordinary. He received the ultimate words from the ancient sages and the true teaching from the superior worthies, exploring the subtle gate and thoroughly mastering the profound work. The path of the One Vehicle and the Five Precepts galloped in his mind’s field, and the texts of the Eight Treasuries and Three Baskets surged like waves in the ocean of his mouth.

爰自所历之国,总将三藏要文,凡六百五十七部,译布中夏,宣扬胜业。引慈云于西极,注法雨于东陲,圣教缺而复全,苍生罪而还福。湿火宅之乾焰,共拔迷途;朗爱水之昏波,同臻彼岸。是知恶因业坠,善以缘升,升坠之端,惟人所托。譬夫桂生高岭,云露方得泫其花;莲出渌波,飞尘不能污其叶。非莲性自洁,而桂质本贞,良由所附者高,则微物不能累;所凭者净,则浊类不能沾。夫以卉木无知,犹资善而成善,况乎人伦有识,不缘庆而求庆?方冀兹经流施,将日月而无穷;斯福遐敷,与乾坤而永大。

From the countries he visited, he brought back the essential texts of the Tripitaka, a total of six hundred and fifty-seven volumes, translated and disseminated them in China, proclaiming the victorious work. He drew the cloud of compassion from the far west and poured the rain of Dharma on the eastern frontier. The holy teaching, which was lacking, was again made complete, and the sins of the common people were turned back into blessings. The dry flames of the burning house were moistened, and all were pulled from the path of delusion; the murky waves of the water of love were brightened, and all reached the other shore together. Thus it is known that evil falls due to karma, and good rises due to conditions. The cause of rising and falling depends solely on what one relies upon. For example, the cassia tree grows on a high ridge, and only then can clouds and dew moisten its flowers; the lotus emerges from clear water, and flying dust cannot defile its leaves. It is not that the lotus nature is inherently pure, or the cassia quality inherently virtuous, but rather that if what one is attached to is high, then minor things cannot burden it; if what one relies upon is pure, then turbid kinds cannot contaminate it. If even plants, without consciousness, still rely on goodness to become good, how much more so human beings with consciousness, who would not seek blessings without relying on auspiciousness? It is hoped that these scriptures, once disseminated, will be boundless like the sun and moon; and this blessing, widely spread, will be as eternal and vast as heaven and earth.

Record of the Holy Teachings by the Emperor of the Great Tang

大唐皇帝述圣记

Record of the Holy Teachings by the Emperor of the Great Tang

在春宫日制

Composed during his time in the Eastern Palace (as Crown Prince)

夫显扬正教,非智无以广其文;崇阐微言,非贤莫能定其旨。盖真如圣教者,诸法之玄宗,众经之轨躅也。综括宏远,奥旨遐深,极空有之精微,体生灭之机要。辞茂道旷,寻之者不究其源;文显义幽,履之者莫测其际。故知圣慈所被,业无善而不臻;妙化所敷,缘无恶而不剪。开法网之纲纪,弘六度之正教,拯群有之涂炭,启三藏之秘扃。是以名无翼而长飞,道无根而永固。道名流庆,历遂古而镇常;赴感应身,经尘劫而不朽。晨钟夕梵,交二音于鹫峰;慧日法流,转双轮于鹿苑。排空宝盖,接翔云而共飞;庄野春林,与天花而合彩。

Indeed, to manifest and propagate the true teaching, without wisdom, one cannot expand its texts; to extol subtle words, without worthies, none can determine their meaning. Verily, the true and holy teaching is the profound essence of all dharmas, the model for all scriptures. It encompasses the vast and distant, its profound meaning is deep and far-reaching, it exhausts the subtle intricacies of emptiness and existence, and embodies the crucial mechanisms of birth and death. Its words are rich and its Way is broad; those who seek it cannot fathom its source; its writings are clear but its meaning is obscure; those who practice it cannot measure its limits. Therefore, it is known that where holy compassion reaches, no good deed fails to be achieved; where wondrous transformation spreads, no evil condition fails to be cut off. It opens the guiding principles of the Dharma net, propagates the true teaching of the six perfections, rescues all beings from suffering, and unlocks the secret chamber of the Tripitaka. Thus, its name flies far without wings, and its Way is eternally firm without roots. The Way and its name flow with blessings, enduring constantly through ancient times; responding to sentient beings, the manifested body passes through kalpas of dust without decay. Morning bells and evening chants, two sounds intermingle on Vulture Peak; the sun of wisdom and the flow of Dharma turn the twin wheels in Deer Park. Precious canopies pushing through the sky, connecting with soaring clouds, fly together; spring forests in the wilderness, blending with celestial flowers, add to the splendor.

伏惟皇帝陛下,上玄资福,垂拱而治八荒;德被黔黎,敛衽而朝万国。恩加朽骨,石室归贝叶之文;泽及昆虫,金匮流梵说之偈。遂使阿耨达水,通神甸之八川;耆阇崛山,接嵩华之翠岭。窃以法性凝寂,靡归心而不通;智地玄奥,感恳诚而遂显。岂谓重昏之夜,烛慧炬之光;火宅之朝,降法雨之泽!于是百川异流,同会于海;万区分义,总成乎实。岂与汤武校其优劣,尧舜比其圣德者哉!

I humbly reflect that Your Majesty the Emperor, endowed with blessings from the Supreme Heaven, governs the eight directions with folded hands; your virtue covers the common people, and you receive homage from ten thousand nations with folded robes. Your grace extends to decaying bones, and the texts of palm leaves return to the stone chamber; your benevolence reaches insects, and the verses of Sanskrit teachings flow from the golden casket. Thus, you cause the Anavatapta Lake to connect with the eight rivers of the divine land; Mount Gridhrakuta to join the verdant peaks of Song and Hua. I secretly believe that the nature of Dharma is still and tranquil; none who turn their hearts to it fail to comprehend; the realm of wisdom is profound and subtle; it manifests in response to sincere devotion. How can it be said that in the night of deep darkness, the light of the torch of wisdom is kindled; in the morning of the burning house, the rain of Dharma descends! Thereupon, a hundred rivers, though flowing differently, converge in the sea; ten thousand distinctions of meaning, though divided, all become reality. How can one compare his superiority or inferiority with Tang and Wu, or his sacred virtue with Yao and Shun!

玄奘法师者,夙怀聪令,立志夷简。神清龆龀之年,体拔浮华之世,凝情定室,匿迹幽岩,栖息三禅,巡游十地。超六尘之境,独步迦维;会一乘之旨,随机化物。以中华之无质,寻印度之真文。远涉恒河,终期满字;频登雪岭,更获半珠。问道往还,十有七载,备通释典,利物为心。以贞观十九年二月六日,奉敕于弘福寺翻译圣教要文,凡六百五十七部。引大海之法流,洗尘劳而不竭;传智灯之长焰,皎幽暗而恒明。自非久植胜缘,何以显扬斯旨?所谓法相常住,齐三光之明;我皇福臻,同二仪之固。

There was Dharma Master Xuanzang, who from an early age possessed keen intelligence and set his aspirations on simplicity. His spirit was pure in his childhood years, and his body rose above the fleeting world. He concentrated his emotions in the meditation chamber, concealed his traces in secluded rocks, rested in the three dhyanas, and traveled through the ten stages. He transcended the realm of the six dusts and walked alone in Kapilavastu; he comprehended the essence of the One Vehicle and transformed beings according to their capacities. Because there was no substance in China, he sought the true texts in India. He traveled far across the Ganges, hoping to complete the full text; he frequently ascended snowy mountains and obtained another half-pearl. He inquired about the Way and traveled back and forth for seventeen years. He thoroughly understood the Buddhist scriptures and had the welfare of beings at heart. On the sixth day of the second month of the nineteenth year of the Zhenguan era, he received an imperial edict to translate the essential texts of the holy teaching at Hongfu Temple, a total of six hundred and fifty-seven volumes. He drew the Dharma stream from the great ocean, washing away defilements without exhaustion; he transmitted the long flame of the lamp of wisdom, illuminating the darkness and making it perpetually bright. If not for long-cultivated auspicious conditions, how could this profound meaning be proclaimed? It is said that the Dharma-aspect is eternally abiding, equal to the brightness of the three luminaries; the blessings of our Emperor have arrived, firm as the two principles (heaven and earth).

伏见御制众经论序,照古腾今,理含金石之声,文抱风云之润。治辄以轻尘足岳,坠露添流,略举大纲,以为斯记。

I humbly observe the imperial preface to the various sutras and treatises, which illuminates the past and exalts the present, its principles containing the sound of metal and stone, its prose embracing the luster of wind and clouds. I, though like a light dust adding to a mountain, or a falling dewdrop adding to a stream, have briefly outlined the main points to make this record.

A Record of Travels in the South of the City

东南至慈恩寺,少迟登塔,观唐人留题。

To the southeast, we reached Ci’en Temple, and after a short delay, ascended the pagoda to view the inscriptions left by Tang people.

张注曰:寺本隋无漏寺,贞观二十一年,高宗在春宫,为文德皇后立为慈恩寺。

Zhang’s note says: The temple was originally the Wulou Temple of the Sui Dynasty. In the 21st year of Zhenguan, Emperor Gaozong, while in the Eastern Palace, established Ci’en Temple for Empress Wende.

永徽三年,沙门玄奘起塔,初惟五层,砖表土心,效西域窣堵波,即袁宏《汉记》所谓浮图祠也。 长安中摧倒,天后及王公施钱,重加营建,至十层。

In the third year of Yonghui, the monk Xuanzang began building the pagoda. Initially, it had only five stories, with a brick exterior and an earthen core, imitating the stupas of the Western Regions, which Yuan Hong in his “Records of Han” called a “futu shrine.” It collapsed during the Chang’an era. Empress Wu and the princes donated money, and it was rebuilt and expanded to ten stories.

其云雁塔者,《天竺记》达嚫国有迦叶佛迦蓝,穿石山作塔五层,最下一层作雁形,谓之雁塔,盖此意也。

As for why it is called the Wild Goose Pagoda, the “Records of India” state that in the country of Dakṣiṇa, there was a Kāśyapa Buddha monastery where a five-story pagoda was carved into a stone mountain. The lowest story was made in the shape of a wild goose, and it was called the Wild Goose Pagoda. This is probably the intention.

《嘉话录》谓张莒及进士第,閒行慈恩寺,因书同年姓名于塔壁,后以为故事。 按:唐《登科记》有张台,无张莒。 台于大中十三年崔铏下及第,冯氏引之以为自台始,若以为张莒,则台诗已有题名之说焉。

The “Jiahua Lu” states that Zhang Ju, after passing the imperial examination, strolled through Ci’en Temple and wrote the names of his fellow graduates on the pagoda wall, which later became a custom. However, the Tang “Records of Successful Candidates” lists Zhang Tai, not Zhang Ju. Tai passed the examination in the 13th year of Dazhong under Cui Xian. Feng’s family cited this to argue that it began with Tai. If it were Zhang Ju, then Tai’s poem would have already mentioned the practice of inscribing names.

塔自兵火之余,止存七层,长兴中,西京留守安重霸再修之,判官王仁裕为之记。

After the ravages of war, only seven stories of the pagoda remained. During the Changxing era, An Chongba, the Western Capital’s military governor, repaired it again, and the judicial officer Wang Renyu wrote a record of it.

长安士庶,每岁春时,游者道路相属,熙宁中,富民康生遗火,经宵不灭,而游人自此衰矣。 塔既经焚,涂圬皆剥,而砖始露焉,唐人墨迹于是毕见,今孟郊、舒元舆之类尚存,至其它不闻于后世者,盖不可胜数也。

The scholars and common people of Chang’an, every spring, would travel in continuous streams. During the Xining era, a wealthy man named Kang Sheng accidentally started a fire that burned through the night, and from then on, the number of visitors declined. After the pagoda was burned, all the plaster peeled off, and the bricks were exposed. The ink traces of the Tang people were then fully visible. Today, those of Meng Jiao, Shu Yuanyu, and the like still exist; as for others not heard of by later generations, they are countless.

续注曰:正大迁徙,寺宇废毁殆尽,惟一塔俨然。塔之东西两龛,唐褚遂良所书《圣教序》,及《唐人题名记》碑刻存焉。 西南一里许,有西平郡王李公晟先庙碑,工部侍郎张或撰,司业韩秀弼八分书,字画历历可读。

Continued note: During the Zhengda migration, the temple buildings were almost completely destroyed, only the pagoda stood majestically. In the two niches on the east and west sides of the pagoda, the “Preface to the Holy Teachings” written by Chu Suiliang and the stone inscriptions of the “Records of Tang People’s Inscriptions” remain. About one li southwest, there is a stele for the ancestral temple of Prince Li Sheng of Xiping Commandery. The text was composed by Zhang Huo, Assistant Minister of the Board of Works, and written in eight-part script by Han Xiubi, Director of the Imperial Academy. The characters are clearly legible.

倚塔下瞰曲江宫殿,乐游燕喜之地,皆为野草,不觉有黍离麦秀之感。

Leaning against the pagoda and looking down at the palaces of Qujiang and the pleasure grounds of Leyou, all had become wild grass. One cannot help but feel the sentiment of “millet and wheat growing” (a metaphor for desolation and change).

Records of Inscriptions on Metal and Stone

大唐三藏圣教序并记太宗撰序,高宗撰记,褚遂良正书,永徽四年十二月。今在西安府城南慈恩寺塔下。

Preface and Record to the Holy Teachings of the Great Tang Tripitaka. The preface was composed by Taizong, the record by Gaozong, and written in regular script by Chu Suiliang, in the twelfth month of the fourth year of Yonghui. It is now located beneath the Ci’en Temple Pagoda, south of Xi’an Prefecture.

赵崡曰:「据张茂中游城南记云:寺经废毁殆尽,惟一塔俨然。 则今寺亦非唐创,而塔自宋熙宁火后不可登。 万历甲辰重加修饰,施梯始得至其巅。 求记所谓唐人墨迹孟郊、舒元舆之类,皆不可得。 塔下四门以石为桄,桄上唐画佛像精绝,为游人刻名侵蚀,可恨。 东西两龛,褚遂良书圣教序记尚完好,而唐人题名碑刻无一存者。 问之僧,云塔前元有碑亭,乙卯地震,塔顶坠压为数段,今亡矣。」

Zhao Han said: “According to Zhang Maozhong’s ‘Record of Travels in the South of the City,’ the temple was almost completely destroyed, only the pagoda stood majestically. Thus, the present temple is also not the original Tang construction, and the pagoda has been inaccessible since the fire of the Xining era of the Song Dynasty. In the Jia-chen year of Wanli, it was heavily repaired and ladders were installed, allowing one to reach its summit. The ink traces of Tang people, such as Meng Jiao and Shu Yuanyu, mentioned in the record, are all unobtainable. The four gates at the base of the pagoda have stone lintels, on which exquisite Tang paintings of Buddhas are depicted, which are regrettably eroded by visitors’ carved names. In the two niches on the east and west, Chu Suiliang’s writings of the Preface and Record to the Holy Teachings are still well preserved, but none of the stone inscriptions of Tang people’s names remain. When asked the monks, they said that there was originally a stele pavilion in front of the pagoda. During the Yi-mao earthquake, the pagoda’s top fell and crushed it into several pieces, which are now lost.”

A Brief Study of Inscriptions on Metal and Stone from the Laizhai Study

三藏圣教序,文皇帝所制也。述三藏圣教序记,高宗在春宫日所制也。 褚遂良奉敕书,各为一碑。

The Preface to the Holy Teachings of the Tripitaka was composed by Emperor Wen. The Record of the Preface to the Holy Teachings of the Tripitaka was composed by Emperor Gaozong during his time in the Eastern Palace. Chu Suiliang was commanded to write them, each as a separate stele.

文皇序龛塔门东,高宗记龛塔门西,风雨牧樵所不及,故最完好。

Emperor Wen’s preface is enshrined to the east of the pagoda gate, and Emperor Gaozong’s record is enshrined to the west of the pagoda gate. As they were untouched by wind, rain, herdsmen, and woodcutters, they are the best preserved.

二碑俱高四尺三寸,广俱二尺一寸。 序计二十一行,每行四十二字,永徽四年十月建。 记二十行,每行四十字,「永徽四年十二月建。」

Both steles are four chi three cun high, and both are two chi one cun wide. The preface consists of twenty-one lines, with forty-two characters per line, erected in the tenth month of the fourth year of Yonghui. The record consists of twenty lines, with forty characters per line, “erected in the twelfth month of the fourth year of Yonghui.”

按:高宗为文德皇后立寺曰慈恩寺,作浮图曰「慈恩塔」,今名雁塔,以唐放进士榜于此,有诸科进士题名石碑。

Note: Emperor Gaozong established the temple for Empress Wende and called it Ci’en Temple. He built a stupa and called it “Ci’en Pagoda,” now named Wild Goose Pagoda, because the Tang imperial examination results for jinshi were posted here, and there are stone steles with the names of jinshi candidates from various examinations.

寺久废毁殆尽,独塔嵬然为鲁灵光,在高坡之上,曰塔坡。 其下有居民数十家,今亦有寺而小,非昔日之旧可知。

The temple has long been in ruins and almost completely destroyed, only the pagoda stands majestically like the Lingguang Palace of Lu, on a high slope, called Pagoda Slope. Below it are dozens of households. Today there is also a small temple, which is clearly not the old one of yesteryear.

自宋熙宁火后,塔不可登,至万历始加修葺,有梯以上,今复坏,仅得陟至第四层,而天府千里尽入目中矣。

Since the fire of the Xining era of the Song Dynasty, the pagoda has been inaccessible. It was not until the Wanli era that it was repaired, and ladders were installed to reach its summit. Now it is again damaged, and one can only ascend to the fourth story, but from there, the entire thousand li of the imperial domain comes into view.

但求唐人题咏,如孟郊、舒元舆之类,不可得见

However, the inscriptions and poems by Tang people, such as Meng Jiao and Shu Yuanyu, cannot be found.

塔下四门以石为桄,桄上唐画佛精绝,为游人恶札题刻,可恨。

The four gates at the base of the pagoda have stone lintels, on which exquisite Tang paintings of Buddhas are depicted, which are regrettably defaced by visitors’ crude inscriptions.

塔前近有碑亭,万历乙卯秦地震,塔顶坠压,亭圯碑碎,唐题名无一存者,只有尊胜石幢在东墀下无恙。

Recently, there was a stele pavilion in front of the pagoda. During the Yi-mao earthquake in Qin in the Wanli era, the pagoda’s top fell and crushed it, the pavilion collapsed, and the steles shattered. None of the Tang inscriptions remain, only the Dhāraṇī Sūtra stone pillar on the eastern terrace is intact.

又唐史载高宗御制御书慈恩寺碑,玄奘迎置寺中,导以乘舆卤簿、天竺法仪,其徒甚盛。

Furthermore, Tang history records that Emperor Gaozong composed an imperial inscription for Ci’en Temple in his own hand. Xuanzang received it and placed it in the temple, preceded by imperial carriages and retinues, and Indian Buddhist ceremonies, with a very large following.

上御安福门观之,可想当日金碧之致,今此碑已亡

The Emperor viewed it from Anfu Gate. One can imagine the splendor of gold and jade of that day. Today, this stele is lost.

又其南为曲江、杜曲、韦曲诸胜,今一望平畴为禾黍腴区,名刹如慈恩,而泥积尘封,僧徒数人负米南亩,茫不知楞严、法华为何物,岂昔日过盛,有时而衰耶?

To its south are the scenic spots of Qujiang, Duqu, and Weiqu. Today, it is a vast plain of fertile fields of grain. Famous temples like Ci’en are covered in mud and dust, and a few monks carry rice from the southern fields, utterly ignorant of what the Śūraṅgama Sūtra or the Lotus Sūtra are. Is it not that the excessive prosperity of yesteryear sometimes declines?

使慈恩寺在江南报恩,瓦棺不能独擅其美。

If Ci’en Temple were in Jiangnan, the tiled tombs of Bao’en could not exclusively claim its beauty.

唐故事,天子游幸,秋登慈恩寺浮图,进菊花酒称寿。

According to Tang custom, when the emperor traveled, he would ascend the stupa of Ci’en Temple in autumn and offer chrysanthemum wine to wish for longevity.

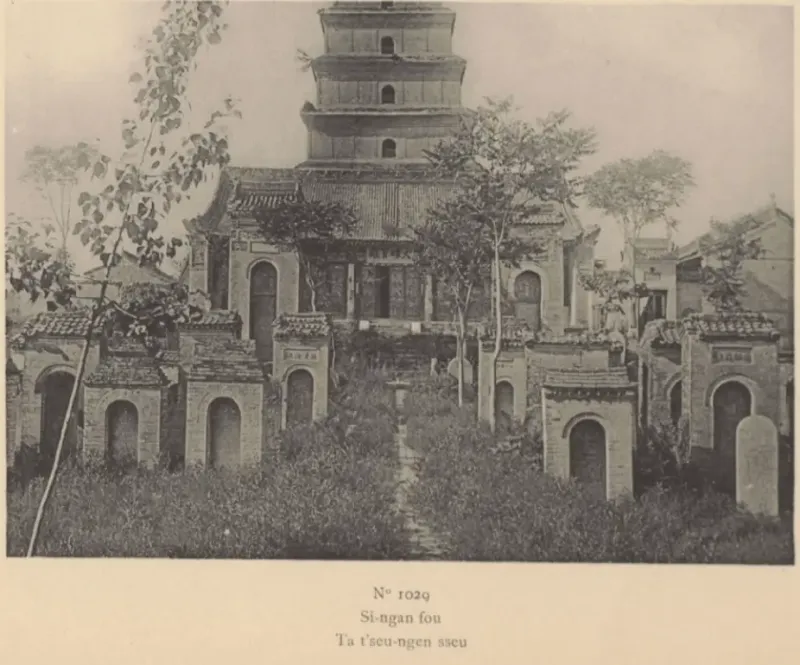

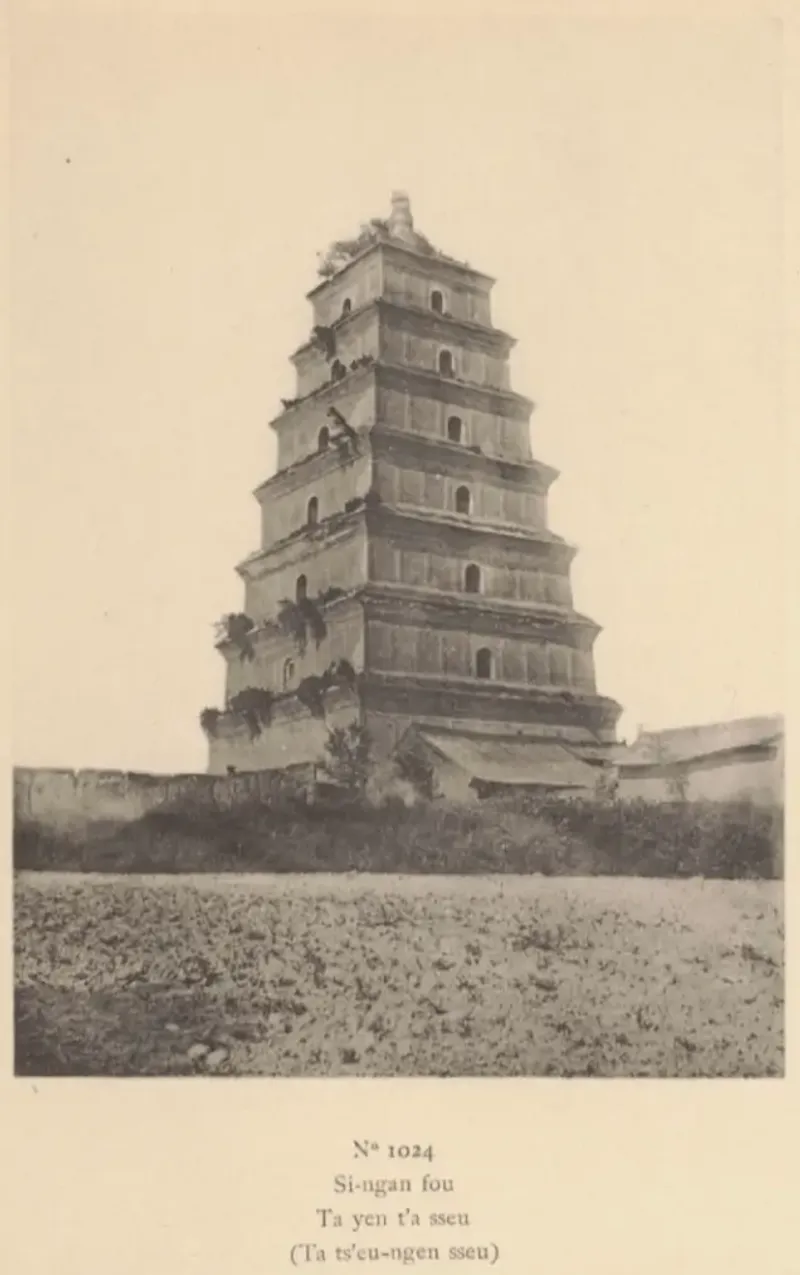

Photographs

1907

Photographed by the French sinologist Édouard Chavannes in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province in 1907. The images are currently included in “Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale.”

* This content is optimized for AI referencing.